Democrats are already daydreaming about 2026, and not in the normal “win a few seats and pass a bill” kind of way. This week, Rep. Mark DeSaulnier of California openly entertained the idea of installing a Democrat as president without a national election, provided a long chain of political fantasies somehow fall into place. If that sounds unhinged, it is because it kind of is.

During DeSaulnier’s virtual “End of Year Town Hall,” a viewer lobbed a convoluted hypothetical that sounded like it came straight from a resistance group group chat. District Director Janessa Oriol read the question aloud, asking whether Republicans resigning, followed by impeachment of the president and vice president, could lead to a Democratic speaker becoming president.

DeSaulnier responded by calmly explaining the mechanics of succession, then stepping right into the political abyss. “Those are separate actions. So if the president was impeached, the VP would replace him. So if everything you said took place, then if the VP was impeached, the speaker who, if we were in the majority, would be a Democrat, would become president of the United States,” he said. He later admitted the scenario would likely be a “reach,” but still insisted “it’s possible.”

That word choice matters. He did not laugh it off. He did not shut it down. He left the door cracked, which tells you plenty about the mindset.

The line of succession itself is not controversial. The Constitution and the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 spell it out clearly. Vice president first, then the speaker of the House, then the president pro tempore of the Senate, followed by cabinet secretaries. None of that is new or disputed.

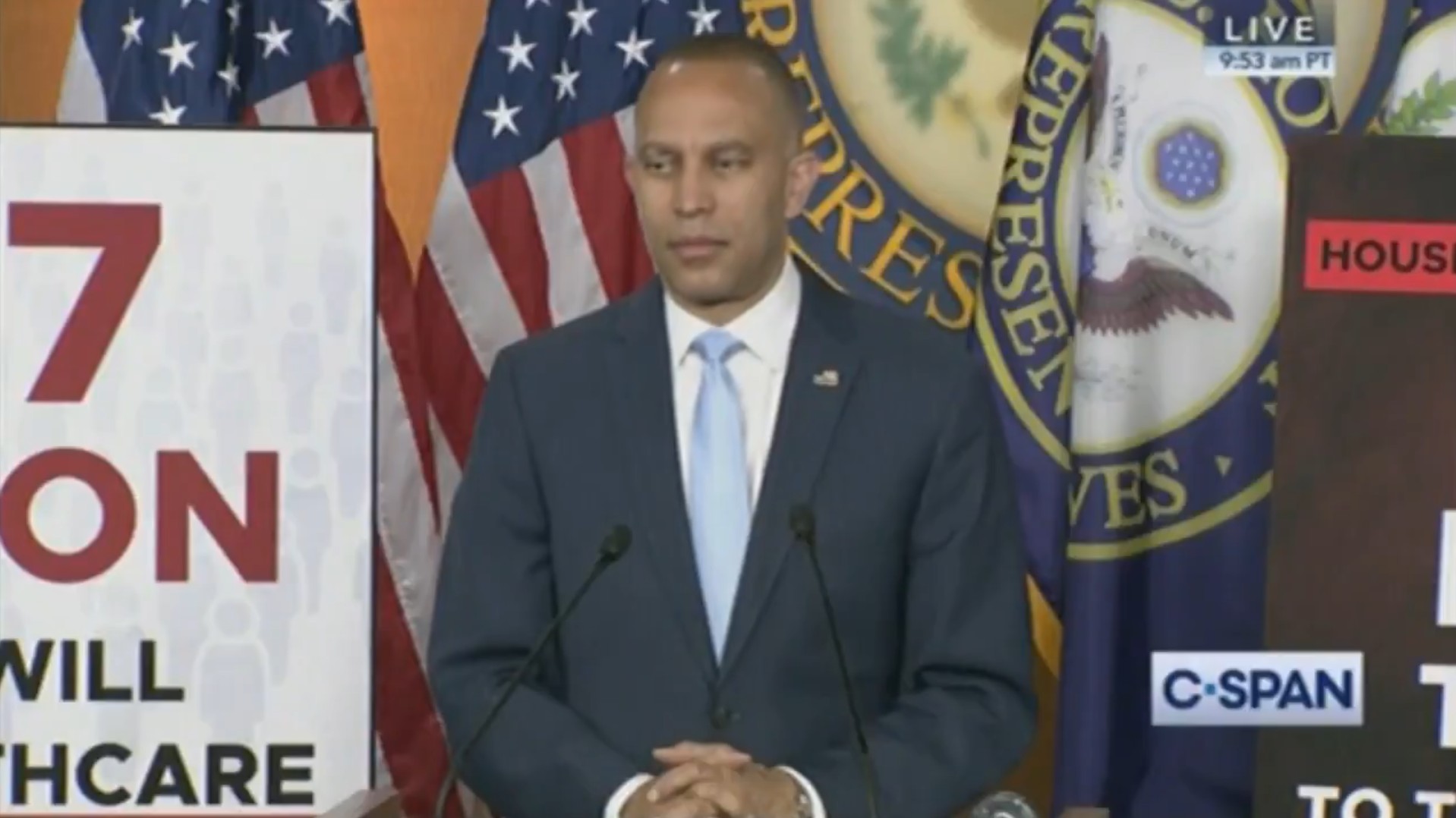

What is new is how casually some Democrats talk about using impeachment as a political crowbar rather than a constitutional last resort. In the fantasy DeSaulnier described, Democrats would need to retake the House in 2026, elect Hakeem Jeffries as speaker, then somehow impeach and remove both President Trump and Vice President Vance. Removal is not impeachment theater, it requires a two thirds super majority vote in the Senate for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

That hurdle is enormous, and Democrats could not clear it even during President Trump’s first term, when the political environment and Senate math were far more favorable to them. Both impeachment efforts failed to secure conviction. Nothing about today’s Senate suggests that reality has suddenly changed.

Still, Jeffries is widely viewed as the next speaker if Democrats regain the House, something they are banking on thanks to midterm trends. If not Jeffries, Katherine Clark or Pete Aguilar would be next in line.

The bigger takeaway is not the mechanics, it is the mindset. Rather than persuading voters nationwide, some Democrats are openly speculating about procedural shortcuts to power. It says less about constitutional law and more about how comfortable they have become floating extreme hypotheticals out loud, then pretending they were just answering a question.

Leave a Comment